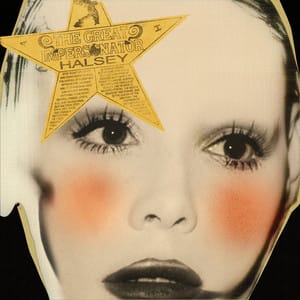

A Verbose, Messy Defense of Halsey’s Verbose, Messy New Album

A review of The Great Impersonator, Halsey's latest concept record.

And some good-old fashioned criticism of criticism

This essay alternates between she and they for Halsey.

I was getting out of a deeply toxic high school relationship when I first heard Halsey. Their first charting hit was the generational-anthem attempt “New Americana,” a post-Lana Del Rey track with the uniquely unconvincing line “high on legal marijuana”, but it was Badlands bonus track “Gasoline” that surprised high school Hannah. The track successfully thrust me into the headspace of one of that person's manic episodes, even as the chorus’ robotic imagery was very dystopian-YA and of its time. Every subsequent album saw Halsey shapeshifting to every pop style in existence, in an attempt to grow beyond the Lorde and Lana Del Rey comparisons of her early music. The only constant was their direct, plainspoken lyricism, clearly inspired by the hyperlexic density of Pete Wentz’s words for Fall Out Boy and Ryan Ross’s words for early Panic at the Disco (for better or worse.) That never fared well with critics, who were hardly fans of either influence to begin with. Because of how direct and unapologetic Halsey was in their presentation, they became a punching bag no matter how big they became.

Let me be extremely clear: “New Americana” is a terrible, pandering song. I don’t blame anyone for thinking of that or the ubiquitous Chainsmokers collaboration “Closer” when they think of Halsey. I don't blame anyone for thinking of overly self-impressed lyrics and half-baked concept albums. When I think of Halsey, I think of the self-destructive melodrama on “Gasoline” or the provocative explorations of gender on If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power. Yes, I also think of clunkers like “Runnin' lines like a marathon/Got it all white like parmesan” (from Hopeless Fountain Kingdom track “Don’t Play”), but those clunkers feel honest instead of forced attempts at humor. The weird thing about Halsey is that she’s an anonymous EDM guest vocalist by trade, a convincing rocker when she wants to be, and an emo kid at heart. That leads to a lot of confusion on whether to take them seriously – my writer friend Kristen S. He referred to Halsey as “a high-concept album artist who makes gigantic crossover hits as a side gig.” The problem is, those concepts don't usually work, claiming Badlands is post-apocalyptic and Hopeless Fountain Kingdom is a genderswapped Romeo & Juliet in interviews when the album never bears this out. On those grounds, Great Impersonator seems like a disaster in the making: a 17-track concept album where every song is inspired by a different artist. Improbably, it's instead her most compelling work to date.

The concept is mostly an excuse to dress up for promo (she’s Tori Amos! She’s Kate Bush! She’s Amy Lee!), and it’s ultimately a red herring. While making the record, Halsey was diagnosed with Ehlers Danlos, lupus, leukemia, and a host of other medical issues on top of their previously existing endometriosis. Within the scope of the album, the tries on all these personas for a reason - complex trauma often results in a fractured sense of self, leaving the person without a coherent view of their own identity. It doesn’t matter how close every song sounds to its inspiration, it’s just a framework for the actual themes. That’s not a reach, either: listen past the cringey wordplay and the intimacy is staggering and almost uncomfortable. Halsey is aware of how others perceive her: “I wonder if I ever left behind my body/Do you think they'd laugh at how I die?”, she sings on the opening track, then deliberately ignores those perceptions for the remainder of the album.

It’s hard not to identify with Halsey’s journey for anyone who’s struggled with similar issues regarding mental health and chronic illness. Though the chord progression is somewhat uninspired as far as Bowie pastiches go, “Darwinism” succinctly depicts the stagnation that comes with neurodivergence: “You all learned something that I fear I'll never know/ You all grew body parts I fear I'll never grow." And that leads into one of the main themes: a yearning to be infantilized throughout the record, nurtured until she can figure herself out again. In recurring songs called “Letter to God”, Halsey wishes as a kid that she could get sick so she could feel loved, only to face multiple chronic illnesses as an adult – it’s delivered almost too directly, but that’s a complex, morbid sentiment in and of itself. On the teaser single “The End”, she sings “If you knew it was the end of the world/Could you love me like a child?” If you didn’t have the hospital fantasy, you’ll have an uphill battle here. If you’re not willing to engage with the record on its own terms at all, you'll enjoy it even less.

TGI is all disjointed and messy, often contradictory in a way that will only further alienate skeptics, but that’s what makes it such a compelling record. Every song is jam-packed with enjambment, lines crashing into the next like they thought it’s the last album it would make (and they did think that!). At the core, Halsey writes in simple couplets, but that’s hard to tell when they come one after the other like they do in “Ego” and “Hometown”. The album eventually recalls Alanis Morrissette’s similarly garrulous sophomore record Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie, but with literal life-or-death stakes instead of Morissette's endearingly myopic Gen-X musings.

Impersonator is a lot like Taylor Swift’s own divisive record Tortured Poets Department in its wordiness (call it Tortured Promo Department, there’s all the snark you’re getting here), only you don’t need extremely specific knowledge of the artist’s life to enjoy it. Yet where that album sounds content to fade away as you’re listening, this one is gloriously over-compressed and overdriven throughout. That would be distracting if it were any other artist. Unlike most records, where the loudness dulls the impact, the constant clipping just adds to the urgency of the album. To paraphrase another misunderstood genre-hopping band, one Halsey probably should have led instead of alleged Scientologist Emily Armstrong: you are going to listen, like it or not. But even if you push everything in the red, even if you scream about how your lover treats you like a burden (as she does on “Life of a Spider”), people still won’t listen.

As a frequent Pitchfork contributor, I don’t get involved in Pitchfork review discourse, but I had to when I read Shaad D’Souza’s disappointing review. D’Souza is a talented writer, but his review lacks the empathy of his exemplary Ethel Cain profile and instead blasts the album purely on aesthetic grounds. Much like the Tweets dunking on every promo shot, it feels more like dispassionate executive feedback than a good-faith take, critiquing a marketing campaign instead of an album. That’s not inherently bad — the impersonation gimmick may serve a purpose, but it is a gimmick funded by Columbia Records and that’s worth noting too. But there’s a fundamental lack of respect surrounding this album. It’s not far off from the lack of respect shown to Chappell Roan or, indeed, Ethel Cain. Hayden Anhedonia, the woman behind Ethel, made a wonderful Tumblr post about earnestness as an autistic trans woman, and how nobody takes her seriously either. In Anhedonia’s words, “everything now is ‘cringe’, or "doing too much’, or "not that serious’. Actually, it is that serious.”

To her point, the worst thing you can do with what’s left of modern pop criticism is try hard and miss. Pitchfork gave Sabrina Carpenter a glowing review because it’s intentionally frothy and fun. But that’s why stans defend her — it’s a fight against misperception by people who’ve felt equally misperceived, no matter how misguided and frankly awful that fight gets. It’s especially difficult to be heard now. We’re in a backlash to the moody therapy-pop of the late-2010s and early-2020s, and a backlash to sincerity unless it comes in lo-res arial font on a green background. If we’re giving grace to pop stars, why not give Halsey the same benefit of the doubt we give Sabrina Carpenter? Just because they’re a little intense? That’s exactly what makes me like them; the total lack of irony when they draw from different inspirations, the lack of pretense in their lyrics even when the concepts behind their albums fall short. For Halsey, there’s zero difference between Bjork and Blink-182, Kate Bush and Evanescence, just more things to draw from. The pastiches are earnest tributes, no self-conscious memes to hide behind, and that’s largely why the album’s surprisingly divisive.

Maybe it’s because I’m trans, and few groups are as willfully misunderstood, but a lot of my writing involves fighting for earnest, misunderstood artists. That gets me some shit from editors when I give some British folkie no one’s ever heard of a 7.2, but I wear it proudly. It’s not just me: Kristen S. He (also trans!) proudly gave Great Impersonator 5 Stars over at NME, and she is the type of person who praises the infamous tinny snare on Metallica’s reviled St. Anger. But sticking up for that snare is contrarianism with purpose; in those ugly overtones, you can hear the hell the band went through to make the record. That doesn’t make St. Anger any good to my ears, but doesn’t make it worth dismissing either.

Fine, it doesn’t make sense to stick up for a highly popular star with billions of streams. I don’t really get high and mighty in my writing – these are all just words. But allow me to say I’m not just defending Halsey. Chronic illness isn’t taken seriously, women’s health isn’t taken seriously, so of course Halsey is not taken seriously just because she sang “I Miss You” in a mall that one time and was the Chainsmokers’ duet partner eight years ago. If you’re going to hate the record, actually hate the record, tell me why the pain doesn’t come across. Tell me about how artless Halsey’s lyrics can get when they’re trying to be direct. Tell me how uninspired the pastiches are: Don’t tell me she’s victimizing herself or has main character syndrome, because it says more about you than you’re saying about the artist.

Even as I take the album on its terms, I know it’s flawed: “Dog Years” sounds the part of 90s grunge, but PJ Harvey would never write something as dumb as “All dogs go to heaven/but what about a bitch.” Fleetwood Mac rip “Panic Attack” is a predictable eye-roll, falling into Halsey’s worst upbeat-song-sad-lyrics cliches and failing to differentiate itself from basically every other Fleetwood Mac rip from the last decade. But somehow, I think it’s close to Halsey’s masterpiece, an unsparingly personal and direct account of life with chronic illness. Despite its missteps, I can’t help but defend it.

And I didn’t even mention G-Eazy in my review! Anyway, Nothing Deep To Say returns next Friday with someone I’m deeply excited to have on, so make sure you're subscribed! If you need a break from election chaos, let this be your tourniquet.